Reman products are a fact of life in the aftermarket. Unlike other product categories, they bring with them some issues that others don’t have to deal with: cores. This month, I’ll discuss cores and the economics of handling them.

For the purposes of this article, we’ll look at one of the most common lines you deal with — brakes. They are the lifeblood of most automotive parts distributors in today’s aftermarket. The largest segments in the brake category are disc brake pads, rotors and calipers. The supply and sale of pads and rotors is relatively straight forward because they are disposable products. Calipers, on the other hand, are a bit more complex because they are a “recycled” or “cored” product. Although reman calipers are on every distributor’s shelf, they don’t get there magically; they depend on the customer (or distributor) for its primary raw material — the core. The role of the remanufacturer is to take the used caliper (core) provided by the customer and refurbish it to like-new (or better) condition. By refurbishing the used calipers, the remanufacturer eliminates the expense of tooling, fabricating and machining the caliper casting. The casting simply gets recycled and the distributor only pays for the value added by the remanufacturer (typically referred to as the “exchange” price).

The underlying premise of the remanufacturing industry is that the distributor owns the core and simply returns cores to the remanufacturer for refurbishing. It is imperative to note that the decision to own a core is made when the distributor decides to get into the caliper business. The first transaction a distributor has with a remanufacturer is typically when a distributor makes its core investment. If you assume that the distributor does not lose any cores, the product line does not change and sales are constant and flat, the distributor won’t need to buy cores again. And so, after the initial transaction, the only out-of-pocket cash for the distributor is the exchange value of the caliper. In the real world, however, calipers get lost, the product line changes and, hopefully, sales increase.

In the case of lost calipers, the distributor must recognize the value of his core investment and protect against inventory shrinkage. For product line changes, most remanufacturers offer an annual stock adjustment in which a distributor can return older, slower-moving SKUs in return for newer, faster-moving ones. It’s important that a distributor take advantage of the annual stock adjustment to prevent core obsolescence (more on this later). An annual stock return is probably the only time a remanufacturer will buy a core from a distributor without requiring the distributor to buy back the same core as a finished product. Lastly, if a distributor is growing his business, periodic core purchases must be made to supplement inventory. For example, if you are carrying four units of a particular SKU and sales are increasing on that SKU, you may need to increase the inventory to six units.

If a distributor manages his core investment properly, the value of the investment is a relatively stable balance-sheet item. One event, however, can dramatically effect a distributor’s core investment: core price devaluation. If a remanufacturer lowers its core price, the value of the core on the distributor’s shelf immediately loses value and must be written down and taken out of income. Generally, a remanufacturer will offer a grace period during which you can return cores at the old, higher price while buying back finished product at the new, lower core price. In this way, the devaluation is largely carried by the remanufacturer. Note that it is unlikely the distributor will turn its entire inventory during the grace period so there is some cost borne by the distributor.

The Economics of Cores

Let’s look at the economics of getting into a cored product like calipers. If you manage your core investment properly, the outlay of cash for the core is done only once, when you first decide to get into the business. After that initial outlay, the cash impact of cores is relatively minimal unless your business is growing very fast.

Let’s look at some hypothetical numbers for one semi-loaded caliper. Let’s assume the average jobber pricing for a semi-loaded caliper is as follows:

Exchange Jobber: $28.00

Core Jobber: $32.00

A distributor will buy this caliper at a discount off the Exchange Jobber. Let’s say a discount of 40 percent, or:

Exchange Cost: $16.80

Core Cost: $32.00

We will also assume the distributor sells the caliper for the Exchange Jobber. Therefore:

Initial Inventory Investment = $16.80 + $32.00 = $48.80

Sales Price = $28.00/Unit

Cost of Sales = $16.80/Unit

Gross Margin = $28.00 – $16.80 = $11.20/Unit

Note: The core is not sold; it is simply exchanged for the used core on the vehicle.

The last two critical assumptions are turns and salvage value.

Regarding turns,many aftermarket distributors report inventory turns between two and three times per year, so we will look at both. The second assumption involves the final (or salvage) value of the unit in inventory. For the purposes of this article, I’ll use a useful life of five years. (Note: This is a conservative estimate. Consider that the best-selling caliper in today’s aftermarket is on GM cars and light trucks from 1988 to 2002 and the average life of the vehicle on the road today is more than nine years). With regard to final value, I will look at a worst case of “zero” final value and a best case of “full” final value. If your supplier has an annual stock adjustment allowance, the full value is really the most likely case.

Based on these figures and assumptions, the decision to go into a cored product like calipers depends if you have other investments competing for your cash that will yield a return in excess of the returns shown above.

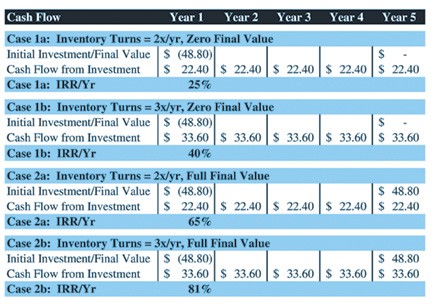

A standard Internal Rate of Return analysis yields the following results:

CORE ACCOUNTING

The examples above show a significant financial incentive for using your annual return allowance.

For financial analysis purposes, the term “inventory turns” is almost always calculated incorrectly on cored products. The standard accounting formula for inventory turns is as follows:

Inventory Turns = Annual Cost of Sales/Total Inventory Investment

Using the figures from our example, most accountants will calculate inventory turns as follows:

Annual Cost of Sales = $16.80/unit x 2 units sold = $33.60

Total Inventory Investment = $48.80

Turns = $33.60/$48.80 = 0.69 turns/year

This result will invariably cause your accountant to tell you that your cored products are not carrying their weight. It’s very important to note that most accountants and banks do not understand cored products and that this conclusion is incorrect. You need to make sure that your accountant understands that cores are not sold and do not turn. The only thing being sold and therefore turning is the exchange value of your inventory. Having a core inventory is conceptually the same as having delivery trucks. You don’t sell your delivery trucks to make money but you need them to be in business. The same is true with cores. Note: The only tangible difference between delivery trucks and cores is that the IRS allows delivery trucks to be carried as a fixed, depreciable asset while cores must be carried as a current, non-depreciable asset. I believe cores should be a fixed and depreciable asset, but I’ve not convinced the IRS of my position.

The correct way to calculate inventory turns on a cored product is:

Annual Cost of Sales = $16.80/unit x 2 units sold = $33.60

Exchange Inventory Investment = $16.80

Turns = $33.60/$16.80 = 2.00 turns/year

Take the time to explain the economics of cored products to your accountant; it will be worth the effort.

As described at the beginning of this article, brakes are the lifeblood for most distributors. What is not shown in these examples is the impact on a distributor’s overall brake business if calipers are not part of their brake program. Most distributors find that they sell more pads and rotors when they carry calipers. A distributor is competing for the first call and service dealers will call a complete-line distributor before they call one that has only a select group of brake products. If you factor in the benefit of higher pad and rotor sales, the return on your caliper investment exceeds the returns shown above.

THREE CORE GUIDELINES

Cored or rebuilt products can be a profitable segment of a distributors business. However, like any other aspect of a successful business, core products must be managed. Here are a few common management mistakes when dealing with a cored product:

1. Don’t try to be everything to everybody. There are 1,800 different caliper sets in use on vehicles dating back to 1970. However, only 200 axle sets are responsible for 90 to 95 percent of the total sales volume. Most remanufacturers can tell you what will sell more than 80 percent of the time in your market. Work with your remanufacturer to dial-in the last 10 to 15 percent to ensure good coverage. Unless you are a specialist, trying to cover more than 90 to 95 percent of sales on a cored product translates into a large core investment and is probably a bad business decision.

2. Don’t use multiple vendors on the same rebuilt product line. Having a core investment in the same rebuilt product with numerous vendors can create a lot of headaches. It’s generally easier to handle cored products if you limit the number of manufacturers for each of your rebuilt product lines.

3. Use the annual clean-up allowance.

Monitor unit turns by part number and take advantage of the remanufacturer’s annual clean-up every year. This is the only way to prevent core obsolescence and maximize your return on investment.